Looking Into Photographs

A look at books about photographs

note: All books mentioned are listed with links at the end.

One of the pleasures of photography is perusing photo-books, letting inspiration in and enjoying the worlds people create with their work. In my practice, I spend time with the past masters and the wonderful work contemporary photographers are making, learning equally from all of them.

“The experience of a truly fine print may be related to the experience of a symphony...” — Ansel Adams

For me, finding meaningful books is a bit random. Randomness is great, but can also be helpful to have a guiding hand, clueing us into what to look for, giving us context around an image, or even just drawing us to images we might not have otherwise thought about.

Required Reading

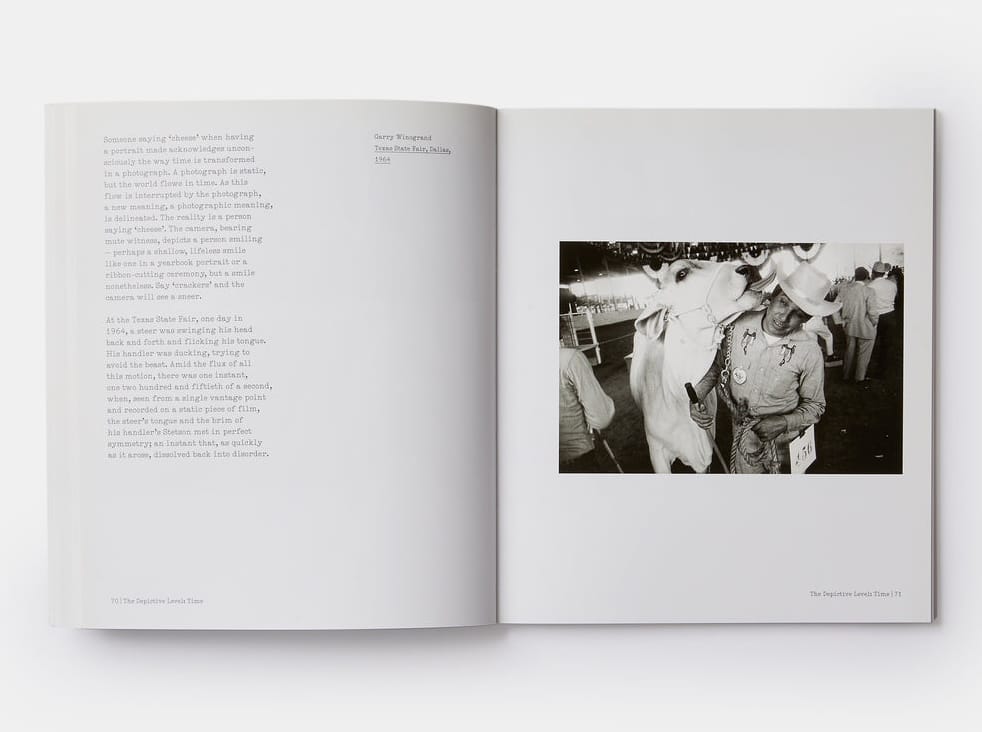

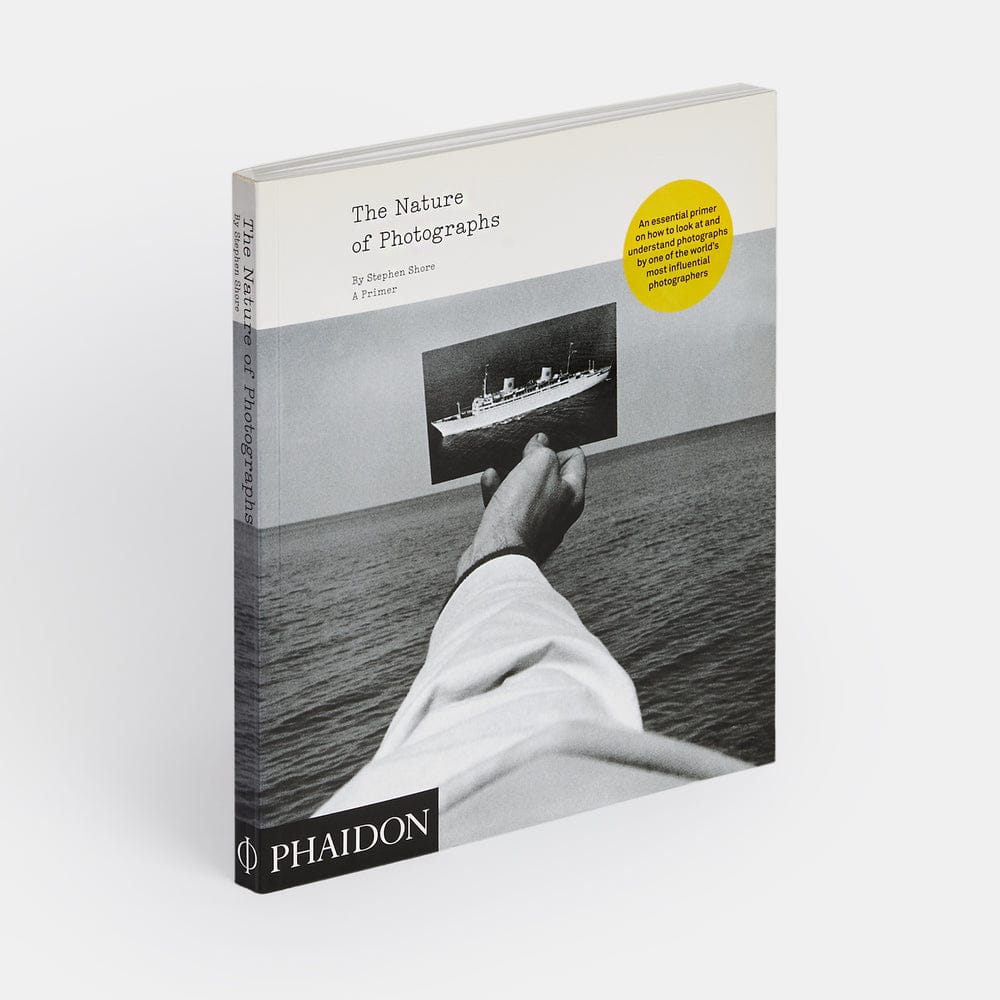

If you read only one, it should be Stephen Shore’s The Nature of Photographs. Shore is not only one of the most significant photographers of the last century, he’s a teacher, too, running Bard College’s photography program. His formal approach is rooted in the history of photography and his deep thought and experience shows even in the very spare prose of this book. He gives you just enough to think differently about photographs he’s chosen:

“A photograph may have a relatively uninflected structure but have recessive mental space.

—Stephen shore, The Nature of Photographs

Though it doesn’t strictly fit with the other books listed here, Shore’s memoir Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography is a master class. In fact, I participated in a master class he gave this year and much of what he discussed can be distilled from both Modern Instances and The Nature of Photographs.

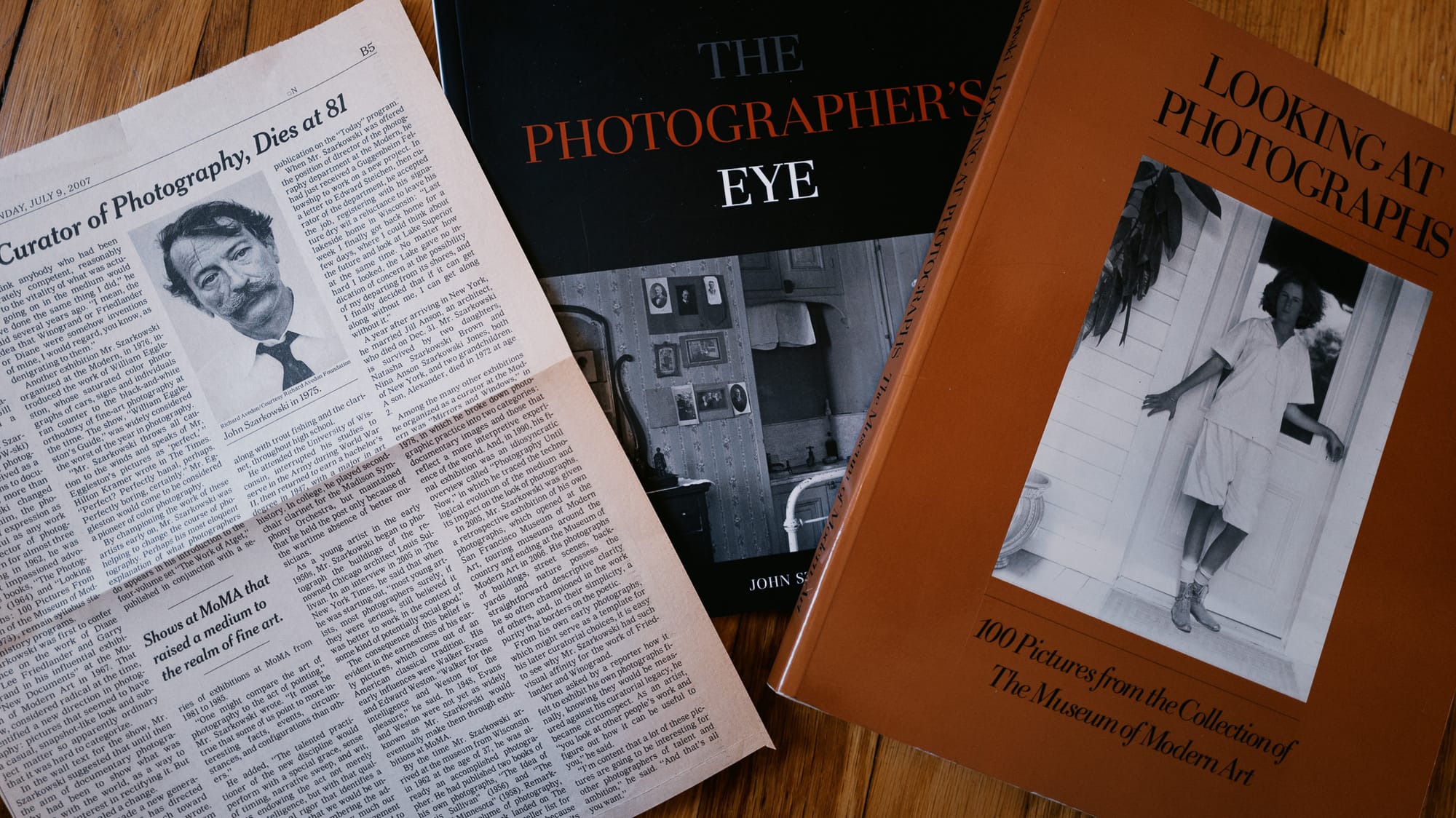

It would be tempting to categorize these books by those written by photographers and those not. But the genre is dominated by critics and curators, the most famous of whom is John Szarkowski, who—famously—ran the Museum of Modern Art’s photography department. While he was indeed a photographer, which shows in his commentary, he was known to the world for surfacing photographer’s work when the art world struggled with what to think about the medium. Szarkowski’s New York Times obituary describes him as “a curator who almost single-handedly elevated photography’s status in the last half-century to that of a fine art…”

With minimal text, The Photographer‘s Eye doesn’t tell you what to think so much as tell you that these images deserve your attention. This collection of photographs from a 1964 exhibit define the possibility in that moment of what an image could accomplish. It is Looking at Photographs that, I think, defines the genre of books on photographs: The paradigm here is a single photograph with a page of brief text. An example:

Two technical aspects of the picture are interesting in terms of their relationship to Modotti’s conception. The two-dimensionality of her picture has been strongly emphasized by the very heavy exposure of her negative, which raised the values of the planes of the picture to a narrow range of light grays; only the thin straight lines of joinery are described as black…

It’s not all that technical, but Szarkowski’s commentary provides not only context but insights such to change the way you look at images. Concluding his thoughts on Irving Penn’s “Woman in Black Dress,” he says:

The true subject of the photograph is the sinuous, vermicular, richly subtle line that describes the silhouetted shape. The line has little to do with women’s bodies or real dresses, but rather with an ideal of efflorescent elegance to which certain exceptional women and their couturiers once aspired.

Bravo! What great writing!

“The artist speaks in terms of his medium; transcription of his ideas in words are almost always inadequate and misleading in the most precise sense.”

— Ansel Adams, “What is Good Photography,” 1940

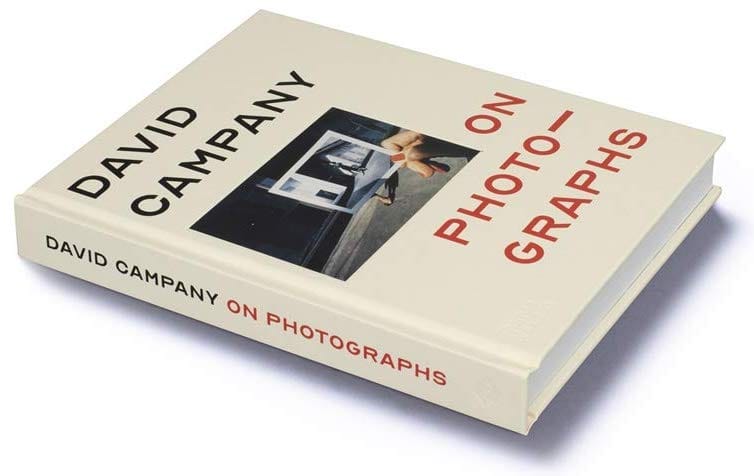

When Looking at Photographs was published, David Campany was just a child in England. Now, he may very well be the heir to Szarkowski’s role of championing curator and erudite commentator. Campany is currently the Creative Director of the International Center for Photography (where I take most of my workshops) in New York City. His book On Photographs pushes photography as fine art even further, highlighting some images that I might describe as anti-photographic art pieces.

For example, Jason Evans’ “Artwork for Four Tet album There is Love in You, 2010” shows us a kaleidoscopic abstract image that Campany tells us ”makes some kind of visual equivalent to the recorded sound,” and oddly, “The design was also intended to to function effectively for all the available formats.”

Elsewhere, he takes a more traditional tack, discussing, for instance, Richard Avedon’s penetrating portrait of the “invention“ of Marilyn Monroe where he the positions the image by talking about the 1956 book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.

It’s an eclectic collection, to be sure, yet in the preface, Campany states what I think could be his thesis:

“…And yet, none of this detracts from the discrete unity of each and every photographic image. Even when put together, they are not exactly like links in a chain, words in a sentence, or even shots in a movie. Each possesses and demands at some measure of individuality. Looking at that individuality has its merits. It can also tell us valuable things about the flux from which it came, and to which, inevitably, it will return.”

The book is valuable in wrenching us out of our way of thinking so we can define for ourselves what makes a great photograph. Campany is one critic photographers should know and read.

Non-Required Reading

“I have been asked many times, ‘What is a great photograph?’ I can answer best by showing a great photograph, not by talking or writing about one.” — Ansel Adams, “A Personal Credo,” 1944

I think there’s a case for not being too practical when reading about images. It's actually just fun, and at the very least slows you down or changes your perspective. Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb bring a rich history and literary point of view to their work and it shows in their book for Aperture’s Workshop series On Street Photography and the Poetic Image.

Here there are no formal or didactic essays, just brief musings on photographs as though you were sitting on a couch with them flipping through images.

The power of Eugene Richard’s photographs come not just from the palpable emotional weight of his subject matter, but also from how the frame edge seems to violate traditional notions of space and form, leaving the viewer suspended, uncertain, wondering at what has been left in the photograph—and what’s been left out. —Alex Webb

"If your pictures aren't good,

you're not reading enough."

— Tod Papageorge

For a lively discussion about the potential of photographs, Geoff Dyer‘s writing is wide-ranging, including his 2018 book on Gary Winogrand. Dyer’s 2005 collection The Ongoing Moment reaches from William Henry Fox Talbot in the beginning of the nineteenth century, to Francesca Woodman in the middle of the twentieth. Along with essays about other writers on photography, See/Saw represents each photographer by an image and short essay:

“Jazz, it is often said, is about being in the moment. By excluding all narrative context DeCarava affirms the importance of the moment while simultaneously expanding it. In one way the shutter speed is too slow to record clearly what is happening in this moment. But this technical failing succeeds in allowing more time to leak into and spill over from the picture.”

The encyclopedic Understanding Photography, by Ian Jeffrey is not so much as inspiring but answers the question of who shaped the medium and what are the essential photographs we should know. It's a dense volume with biographies and capsule interpretations, making this book valuable for your library, though not likely one you'd read from front-to-back.

Maybe Skip, Unless That's Your Thing

My point of view here is that of a photographer. These are indeed valuable books, but more so for those into curation, philosophy or criticism.

The Photograph as Contemporary Art answered (or attempts to answer) a pressing question in my mind: What makes a photograph Art? The answer would appear that contemporary art tends to eschew form for meaning where the image only speaks for itself as much as it has cultural currency. That is not, admittedly, a fair or complete characterization, but it left me feeling that the only way to create art is to be an Artist.

Graham Clarke asks early on in The Photograph, “How do we Read a Photograph” and in answering sucks much of the joy out of doing so! Harsh, I know, but as a photographer aiming to invest their energy into learning from others‘ work, I’ve mostly steered clear of writing on photography in a philosophical or societal context (for example, Sontag and Barthes, the oft cited duo of photography writing who I find depressing). Still, The Photograph is worth reading for historical context and perhaps an introduction to a way of critical thinking; just don't expect it to help inform your own work.

Books Mentioned

Books are linked to the author or publisher, when available, or otherwise used-bookstore or the Internet Archive

Stephen Shore

John Szarkowski

David Campany

https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262044240/on-photographs/

Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb

Geoff Dyer

https://geoffdyer.com/books/the-ongoing-moment/

https://geoffdyer.com/books/see-saw-looking-at-photographs-2010-2020-2/

Ian Jeffrey

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Understanding-Photography/Ian-Jeffrey/9789493039445

Charlotte Cotton

Graham Clarke

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-photograph-9780192842008

Other Resources

These Youtube channels look at Photographers' work

“I have been asked many times, ‘What is a great photograph?’ I can answer best by showing a great photograph, not by talking or writing about one.”

— Ansel Adams, “A Personal Credo,” 1944